82 acres of earth is slipping downhill at Keene Valley

On May 6, the iris garden alongside Jim and Charity Marlatts’ house on a mountain two hours north of Albany was cleaved by a small crack only two inches wide. It was the start of a natural catastrophe, one that is still unfolding at an excruciatingly slow pace.

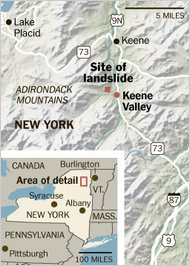

The Marlatts’ treasured glass and wood retirement home is now on the scarp — the geologic term for the edge above — of the largest landslide in New York State history. About 82 acres of earth is slipping downhill and taking trees, rocks and houses with it.

But unlike the landslides that occur in a rush as debris breaks free, usually after a torrential rain or earthquake, this one is occurring incrementally, moving anywhere from two inches to two feet per day. Within weeks, the crack in the garden extended nearly a mile and as the land on the downhill slope began sliding away toward the valley, it created a step that is now a 20-foot vertical drop. Half of the flowers and half of the property beneath the Marlatts’ house went with the sliding mass. Before long, their master bedroom and dining room were hanging over the cliff’s edge.(PoleShift.ning/12Planet)

When Nature Destroys in Slow Motion

Ask and geologists will say that landslides are much more common than people realize. The United States Geological Survey estimates that they occur in every state and each year kill on average 25 people nationally while wreaking $1 billion to $2 billion in damage. Yet they are perhaps the least studied of the natural disasters and difficult to anticipate, said Francis Ashland, a research geologist with the survey.

Slow-moving landslides are also not uncommon, particularly in the West. For example, geologists have been following a very slow slide in North Salt Lake City, Utah, that has been on the move since 1998.

New York State is not generally perceived as landslide territory, but in mountainous areas upstate there are quite a few. The last really large one occurred in Tully Valley, just south of Syracuse, in 1993, during which several homes and dozens of acres of cropland were ruined. Albany and Schenectady have also been the sites of smaller but still costly slides.

New York State is not generally perceived as landslide territory, but in mountainous areas upstate there are quite a few. The last really large one occurred in Tully Valley, just south of Syracuse, in 1993, during which several homes and dozens of acres of cropland were ruined. Albany and Schenectady have also been the sites of smaller but still costly slides.

The high peaks around Keene and the Finger Lakes Region have been found to be particularly susceptible to the slides because of loose soil deposited on bedrock and formed by glacial lake sediment thousands of years ago, said Andrew Kozlowski, the associate state geologist with the New York State Museum and director of its geological mapping program.

For geologists, figuring out the timing and location of the slides is the real challenge. This has been an active year for slides from Burlington, Vt., to Pittsburgh, said Dr. Ashland, who is studying their underlying cause and rate of occurrence. Western Pennsylvania currently has the highest landslide hazard in the country.

Abnormally heavy snows and spring rains prompted the Keene Valley slide, said Dr. Kozlowski, who is the lead scientist here. To his trained eye, it is clear that there were landslides on this slope before, but hundreds of years ago.

He said this landslide, about a mile wide, was probably set off as groundwater built up and eventually loosened soil as deep as 80 feet. Once surface cracking began, it allowed more water in, and now the whole side of the hill, 60 to 80 feet down, is on the move. While the actual motion is not detectable to human feet, residents and scientists alike are wary of moving about the slide because occasionally a tree is felled or a boulder is loosened and sent rushing down the slope.

The toe of this landslide, or the bottom, is flowing slowly out on a field in the valley. There, it has already cracked trees and an electric pole and is threatening a farmhouse, about 50 yards away across a dirt road, that Dr. Kozlowski predicts will be damaged within the year.

He will not venture a guess as to when the flow might cease. “It could be three months or three years or longer, depending on rainfall,” he said.

It is theoretically possible to mitigate a slow slide through extensive drainage and by buttressing the toe, but Dr. Ashland said such work was expensive and often did not pass a cost-benefit analysis. He added this would certainly be the case in Keene Valley. (NYTimes)

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules:

We reserve the right to remove any comments that violate these rules. By commenting on our website, you agree to abide by these guidelines. Thank you for helping to create a positive and welcoming environment for all.