Pine Island Glacier’s calving front free of sea ice

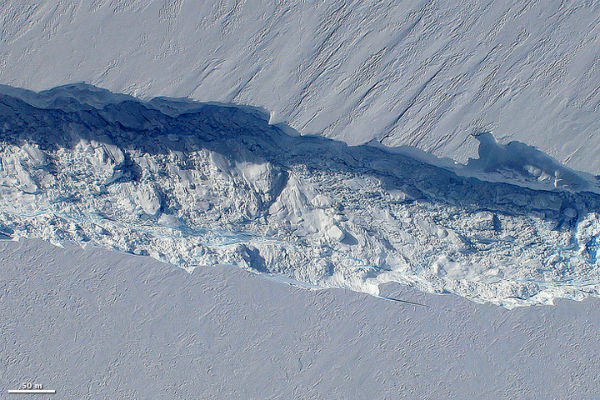

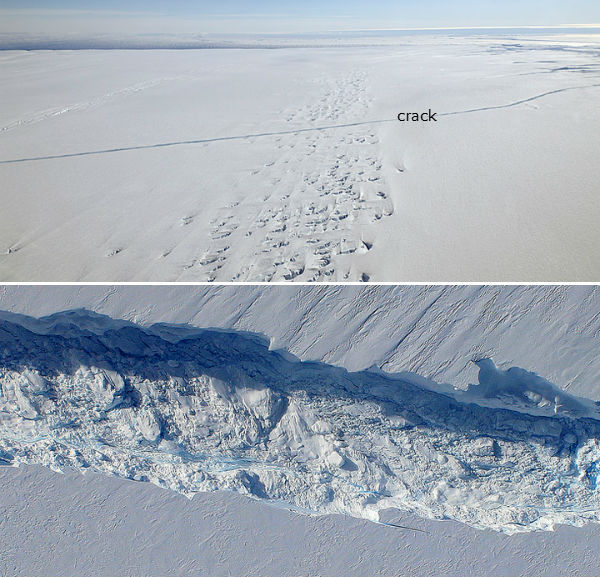

Flying over the Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier last year in October, NASA’s Operation IceBridge scientists discovered a massive rift 29 kilometers (18 miles) long, 80 meters (260 feet) wide on average, and 50 to 60 meters (170 to 200 feet) deep. When that crack reaches the other side of the ice shelf, it will send a huge new iceberg drifting into Pine Island Bay.

Satellite image from October 26, 2012 acquired by the Enhanced Thematic Mapper (ETM) on Landsat 7, shows the rift still had a few more kilometers to go before reaching the other end of the ice shelf. Much of the floating sea ice has cleared away from Pine Island Glacier’s calving front due the arrival of spring in Antarctica.

(NASA Earth Observatory image created by Matthew Radcliff, using Landsat data provided by the United States Geological Survey. Caption by Adam Voiland, information from Jefferson Beck and Kelly Brunt. October 26, 2012 ETM/Landsat7)

(NASA Earth Observatory image created by Matthew Radcliff, using Landsat data provided by the United States Geological Survey. Caption by Adam Voiland, information from Jefferson Beck and Kelly Brunt. October 26, 2012 ETM/Landsat7)

Scientists suspect that the absence of sea ice may hasten break off an iceberg. The fact that there’s no sea ice in front of Pine Island Glacier right now implies that it might be primed to calve, according to NASA glaciologist Kelly Brunt. Ice calving is the sudden release and breaking away of a mass of ice from a glacier, iceberg, ice front, ice shelf, or crevasse. The ice that breaks away can be classified as an iceberg, but may also be a growler, bergy bit, or a crevasse wall breakaway. Calving of glaciers is often preceded by a loud cracking or booming sound before blocks of ice up to 200 feet high break loose and crash into the water. The entry of the ice into the water causes large, and often hazardous wakes. The wakes formed in locations like Johns Hopkins Glacier can be so large that boats cannot approach closer than two miles. Calving of ice shelves is usually preceded by a rift.

The upper photo was taken by a passenger on the jet, while the Digital Mapping System took the lower photo on October 26, 2011, when scientists returned to survey the glacier in greater detail. (Source: Earth Observatory)

The upper photo was taken by a passenger on the jet, while the Digital Mapping System took the lower photo on October 26, 2011, when scientists returned to survey the glacier in greater detail. (Source: Earth Observatory)

Pine Island Glacier is one of the fastest moving glaciers in Antarctica. It drains about 79 cubic kilometers (19 cubic miles) of ice per year from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The end of the glacier stretched about 48 kilometers (30 miles) past the edge of land, floating on the ocean. As more ice flows toward the water, the tongue grows longer. Eventually, a piece will break off, forming a large iceberg. The last calving event occurred in late 2001 and resulted in an iceberg that measured 42 kilometers by 17 kilometers (26 by 11 miles). That event, too, was preceded by a large crack that was observed in satellite imagery in late 2000.

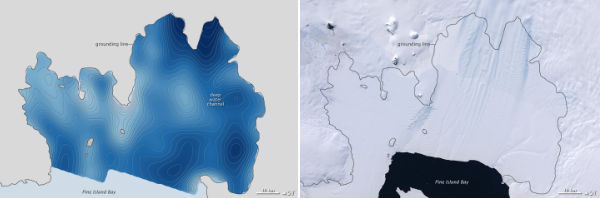

Scientists participating in NASA’s Operation IceBridge mapped the water depth and seafloor topography beneath Pine Island Glacier and found a deepwater channel – a likely pathway for warm water to reach the glacier’s underbelly and melt it from below. (NASA Earth Observatory images created by Jesse Allen, based on a model by Michael Studinger of NASA IceBridge and gravity data from Columbia University)

Scientists participating in NASA’s Operation IceBridge mapped the water depth and seafloor topography beneath Pine Island Glacier and found a deepwater channel – a likely pathway for warm water to reach the glacier’s underbelly and melt it from below. (NASA Earth Observatory images created by Jesse Allen, based on a model by Michael Studinger of NASA IceBridge and gravity data from Columbia University)

IceBridge scientists were surveying the Pine Island Glacier to learn how the glacier is changing and why. In the largest airborne survey of Earth’s polar ice, the airplanes of Operation IceBridge carry an array of instruments to measure the ice from top to bottom. The research team is gathering data about how thick the ice is (about 500 meters or 1,640 feet in the region of the crack); what the ground beneath it looks like; and how the glacier has changed over time. All of this information will help scientists understand why the Pine Island Glacier drains so much ice to the ocean and how much it could contribute to sea level rise in the future.

More photos and a video of the crack in the glacier are available on the IceBridge website and on the NASA Ice photostream.

IceBridge: Building a record of Earth’s changing ice, one flight at a time

Source: Earth Observatory

NASA images courtesy Digital Mapping System team and Michael Studinger

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.