Gravitational lensing – NASA's great observatories begin deepest ever probe of the universe

NASA's Hubble, Spitzer and Chandra space telescopes are teaming up to look deeper into the universe than ever before. With a boost from natural "zoom lenses" found in space, they should be able to uncover galaxies that are as much as 100 times fainter than what these three great observatories typically can see now.

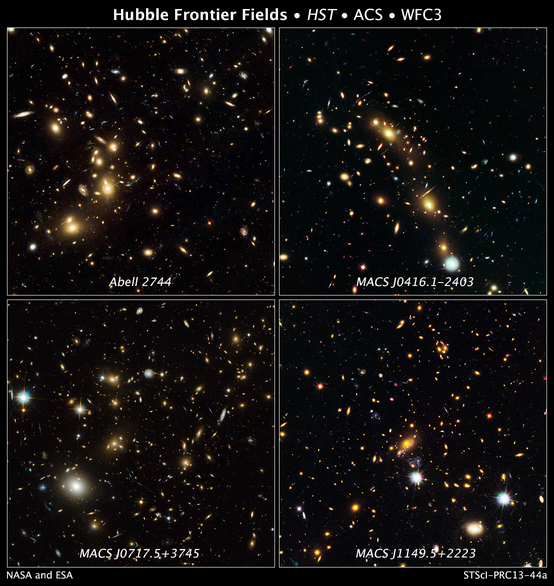

In an ambitious collaborative program called The Frontier Fields, astronomers will make observations during the next three years peering at six massive clusters of galaxies, exploiting a natural phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, to learn not only what is inside the clusters but also what is beyond them. The clusters are among the most massive assemblages of matter known, and their gravitational fields can be used to brighten and magnify more distant galaxies so they can be observed.

Abell 2744, commonly known as Pandora's Cluster, is he first object they will view is The giant galaxy cluster appears to be the result of a simultaneous pile-up of at least four separate, smaller galaxy clusters that took place over a span of 350 million years.

Astronomers anticipate these observations will reveal populations of galaxies that existed when the universe was only a few hundred million years old, but have not been seen before.

"The idea is to use nature's natural telescopes in combination with the great observatories to look much deeper than before and find the most distant and faint galaxies we can possibly see," said Jennifer Lotz, a principal investigator with the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Md.

These are NASA Hubble Space Telescope natural-color images of four target galaxy clusters that are part of an ambitious new observing program called The Frontier Fields. NASA's Great Observatories are teaming up to look deeper into the universe than ever before. With a boost from natural "zoom lenses" found in space, they should be able to uncover galaxies that are as much as 100 times fainter than what the Hubble, Spitzer, and Chandra space telescopes can typically see. The gravitational fields of the clusters brighten and magnify far-more-distant background galaxies that are so faint they would otherwise be unobservable. The foreground clusters range in distance from 3 billion to 5 billion light-years from Earth. Image credit: Credit: NASA, ESA, and J. Lotz and M. Mountain (STScI)

Data from the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes will be combined to measure the galaxies' distances and masses more accurately than either observatory could measure alone, demonstrating their synergy for such studies.

"We want to understand when and how the first stars and galaxies formed in the universe, and each great observatory gives us a different piece of the puzzle," said Peter Capak, the Spitzer principal investigator for the Frontier Fields program. "Hubble tells you which galaxies to look at and how many stars are being born in those systems. Spitzer tells you how old the galaxy is and how many stars have formed."

The Chandra X-ray Observatory also will peer deep into the star fields. It will image the clusters at X-ray wavelengths to help determine their mass and measure their gravitational lensing power, and identify background galaxies hosting supermassive black holes.

High-resolution Hubble data from the Frontier Fields program will be used to trace the distribution of dark matter within the six massive foreground clusters. Accounting for the bulk of the universe's mass, dark matter is the underlying invisible scaffolding attached to galaxies.

Hubble and Spitzer have studied other deep fields with great success. The Frontier Fields researchers anticipate a challenge because the distortion and magnification caused by the gravitational lensing phenomenon will make it difficult for them to understand the true properties of the background galaxies.

Goddard Space Flight Center explains gravitational lensing

Imagine a bright object such as a star, a galaxy, or a quasar, that is very far away from Earth (say…10 billion light years). For our discussion, let us imagine we have a quasar.

If there is nothing between it and us, we see one image of the quasar. Yet, if a massive galaxy (or cluster of galaxies) is blocking the direct view to the quasar, the light will be bent by the gravitational field around the galaxy [see figure below]. This is called "gravitational lensing," since the gravity of the intervening galaxy acts like a lens to redirect the light rays.

Rather than creating a single image of the quasar, the gravitational lens creates multiple images. We follow the light rays from the Earth to the apparent locations of the quasar. If the galaxy were perfectly symmetric with respect to the line between the quasar and the Earth, then we would see a ring of quasars.

Image credit: High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center (HEASARC) – GSFC

Learn more about gravitational lensing here.

Sources: NASA/Chandra, Hubble, GSFC

Featured image: Abell 2744, Pandora's Cluster. Image credit: NASA, ESA, and R. Dupke (Eureka Scientific, Inc.), et al.

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules:

We reserve the right to remove any comments that violate these rules. By commenting on our website, you agree to abide by these guidelines. Thank you for helping to create a positive and welcoming environment for all.